I know I’ve said it before, but whatever, I’m saying it again: 2016 has been an awful year.

Both personally and globally, it’s been the total pits, to the point that I’m already planning on countering any complaint my future grandchildren make in life with, “At least you didn’t have to experience 2016.”

With that said, 2016 is almost over (thank God). As we approach 2017, we don’t know what will come, but the least we can do is welcome it with some good news.

While in so many other ways, the world has gone backwards, sideways, and completely off the rails this year, medical advancements continue at a steady, progressive pace.

Sickle cell anemia is one of the most recent conditions to benefit from such strides.

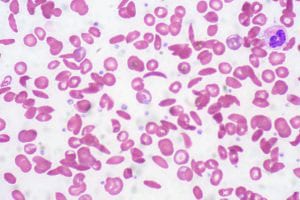

Passed through the recessive gene, sickle cell anemia is an inherited condition that causes red blood cells to change shape, becoming rigid, sticky, and sickle-like (hence the name).

These mutated cells can’t travel as easily, which results in blockages and less oxygen traveling through the body.

The condition can be painful, on top of the other complications that come with it.

Fortunately, at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, researchers have made major gains for sickle cell anemia by exploring a technique known as “forced chromatin looping.”

The Jupital has a great scientific explanation of what researchers are trying to accomplish with this technique, but the short of it is, they may be able to restore functionality to the blood cells by producing foetal hemoglobin. This kind of hemoglobin (hemoglobin being the part of the blood cell that carries oxygen) isn’t affected by sickle cell.

The problem right now is that foetal hemoglobin doesn’t hang around much after birth. Hopefully with the new technique, researchers will find a way to restart that production in humans once they’ve aged.

This could be a big development for those living with sickle cell anemia.

I, for one, can’t wait to say goodbye to 2016 and move that much closer to a future where this research comes to its promised conclusion.

Read more about the research here.

What do you hope next year brings in terms of medical advancement? Share your 2017 wish lists below!