According to an article published by Washington University of Medicine in St. Louis, scientists appear to have succeeded in slowing axon destruction in mice through standard gene therapy. Though an extremely early step in the clinical trial process, successful animal testing is often the last port of call before a proposed treatment begins human testing.

What are Axons?

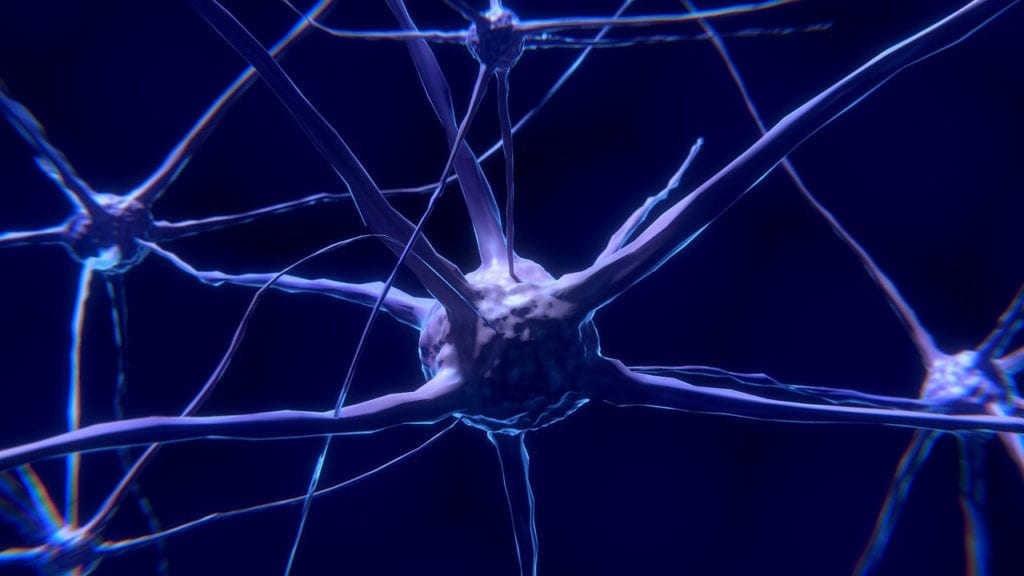

Axons are long, slender tendrils that are one of the major components of nerve cells. Axons act kind of like the barrel of a gun, transmitting action impulses (electrical charges) away from the center of the neuron along their length to the synaptic terminals – where the charges are converted to chemical signals and “fired” across a small gap to another neuron. This is how nerve cells communicate with one another, meaning axons play a pretty important role in how the body functions.

Certain drugs and medical conditions can damage axons. This triggers an automatic “self-destruct” response in the axons, causing them to break apart and cease to function. Scientists believe this is related to the activation of a protein called SARM1.

SARM1 seems to be absent, or at least passive in healthy nerve cells. When an axon is damaged however, SARM1 is released, kicking off the “self-destruct” sequence.

Gene Therapy to Solve Axon Destruction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease, peripheral neuropathy, and potentially more seem likely to be related to this axon destruction process.

That’s why scientists were eager to discover that a modified version of the SARM1 protein showed promising results in suppressing axon destruction in mice with nerve damage.

Viruses are incredibly small, which make them really good at penetrating the body’s defense mechanisms. Scientists use this to their advantage my modifying otherwise harmless viruses to sneak modified genetic material into cells. These modified genetic materials can activate, shut down, or otherwise manipulate cell function.

Research from the Washington University of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that such techniques may be used to deliver a modified form of the SARM1 protein into patients experiencing axon destruction in the future. In mice, the modified SARM1 protein was able to block the function of normal SARM1 molecules, thereby slowing the progression of axon destruction following initial damage.

Gene therapy has existed for some time now, but scientists are only just beginning to scratch the surface of its potential. Theoretically, researchers may even be able to target what kind of cells the modified virus targets, like sensory or motor neurons. This could limit the amount of modified SARM1 needed for each patient.

Since the reported findings were only in animals, it’s important to keep any hype in perspective. However, researchers are eager to probe the findings further – such a treatment could potentially affect millions of people with dozens of different conditions.

Animal research is an important step in establishing clinical testing, but often has little to do with establishing efficacy in humans. Do you think it’s good or bad that animal test results are publicized? Share your thoughts with Patient Worthy!