According to a publication from Neuroscience News, a team of researchers has managed to examine how amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) progresses on a cellular level for the first time. The research required the use of a groundbreaking medical technique, and intensive data analysis. According to Tarmo Äijö, a lead scientist on the project and researcher at the Center for Computational Biology at the Flatiron Institute, international collaboration was a necessary part of the formula for success as well.

“We all brought different skills to the table,” Äijö said. Scientists in Stockholm take measurements for ALS experts at the New York Genome Institute, who in turn provide the relevant data to the Flatiron Institute for analysis. “This couldn’t happen without all of us.”

About Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a group of rare neurological conditions affecting the neurons that control voluntary movement. Most often ALS occurs sporadically, in individuals with no associated family history – though about 10% of cases are genetically inherited.

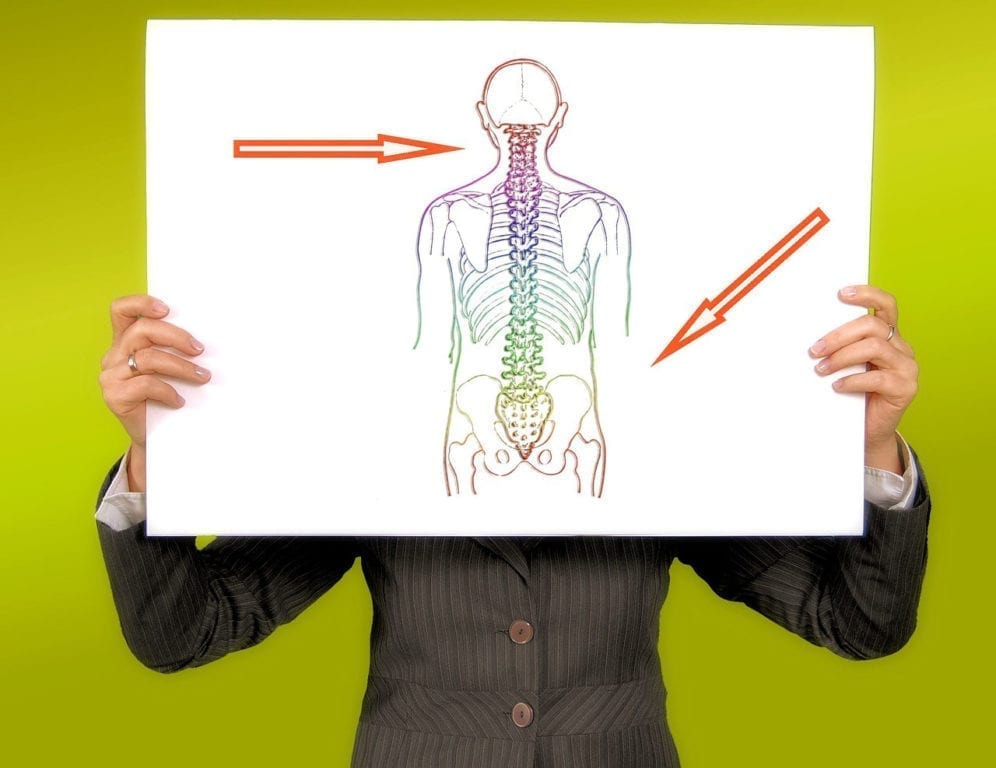

It’s caused by a steady degeneration in the motor neurons linking the brain to the spine, and the spine to various muscles. As these neurons degenerate, difficulties moving grow increasingly pronounced. Early, mild symptoms that typically first suggest the presence of ALS include cramping, slurred speech, or stiffness. Late stages of the disease are characterized by complete loss of voluntary motion – even including breathing.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure what triggers non-genetic cases of ALS, but the current consensus is that genetic mutations and environmental factors like exposure to airborne toxins are co-responsible in varying degrees.

About the Study

By examining incredibly thin segments of spinal cord tissue from thousands of mice and 80 postmortem human spinal tissue donations, the researchers were able to plot the progression of the disease “over time” as it affected the spinal tissue.

In humans, ALS typically begins towards one end of the spinal cord and moves its way toward the other end. To study this effect, the researchers took tissue samples from both ends of the spine. By taking these samples and thinly dividing them, researchers were able to piece together a sort of high-tech “flipbook” suggesting how ALS spread from one area to another.

The team later published their findings on an “interactive data exploration portal,” which you can find here! There are pictures!

Do you think international cooperation will be an important part of the biggest medical discoveries of the next century? Patient Worthy wants to hear your thoughts!