Written By: Teonna Woolford

As a child, I never saw myself as anything but “normal.” I loved going to the playground with my friends and jumping rope. My parents encouraged me to challenge myself academically, and I thrived in school. People probably didn’t notice that I was living with sickle cell disease (SCD), a rare and potentially life-threatening condition. But when I began developing complications related to SCD during my teenage years, I knew I could no longer ignore the role the disease played in my life. I am now 30 years old and proud to say that SCD has shown me my purpose in life rather than keeping me from achieving my goals.

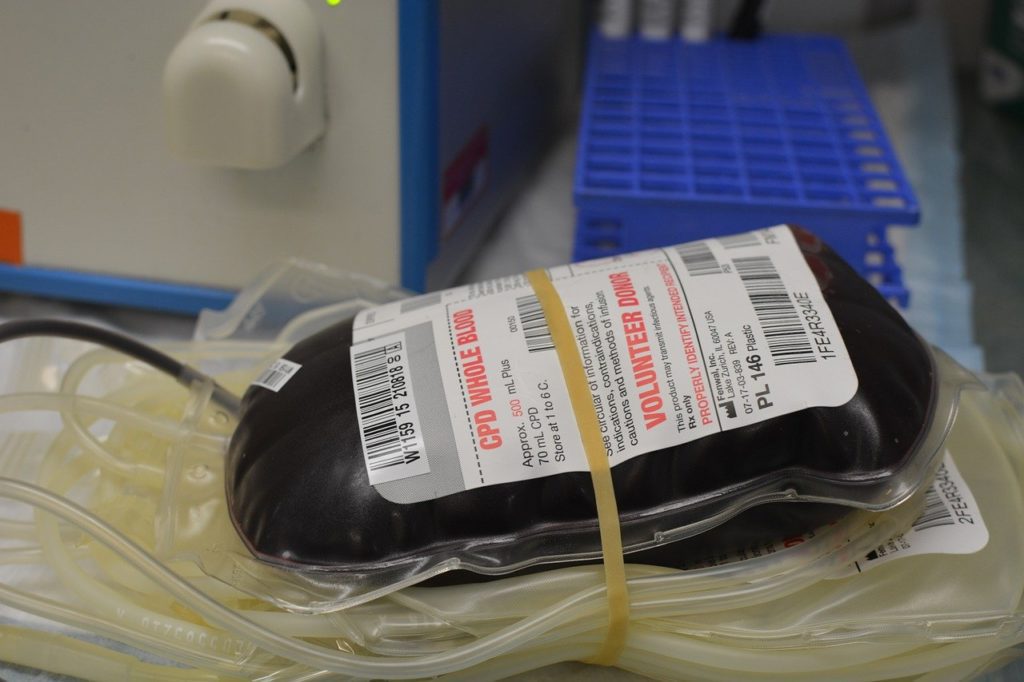

SCD is a genetic disorder that causes the red blood cells to form in a sickle shape. This malformation affects their ability to transport oxygen in the blood throughout the body. As a result, patients can experience anemia, severe pain crises, infections, stroke, and organ damage. SCD is most commonly seen in patients of African descent, but it is also prevalent among the Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian, and Mediterranean populations. There are treatments available to address certain symptoms of the disease, but there are no approved medicines that target the genetic root cause of SCD.

My pain crises were infrequent when I was a child, and when they occurred, blood transfusions provided relief. But after I turned 14, my condition seemed to spiral out of control. The pain crises became more frequent and seemed completely unpredictable. I experienced a life-threatening complication, known as acute chest syndrome, multiple times, and the frequent blood transfusions I needed eventually caused me to go into liver failure. By the time I was 16 years old, both of my hips were replaced after I developed avascular necrosis—my bone tissue in the joints died after receiving an insufficient blood supply. By the time I was 18 years old, doctors discovered that my bone marrow was not producing adequate numbers of red blood cells. They recommended that instead of going to college with my friends, I stay behind and undergo a bone marrow transplant so that my body would be able to produce the healthy blood of a donor rather than my own.

I knew the transplant was my only chance at having a life free from SCD and decided to move forward with the process. I underwent a month-long hospital stay and was given strong chemotherapy and radiation treatments that caused me to lose my hair, develop infections, and experience painful side effects. I struggled with knowing that these treatments would also leave me infertile. In fact, it was my only source of hesitation when deciding to undergo the transplant. After all of these struggles, I found out that my body hadn’t accepted the donor bone marrow. The transplant failed.

My experiences showed me how important it is to raise awareness of the toll SCD takes on patients and their families. I began sharing my story with the National Institute of Health (NIH), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and several pharmaceutical companies. I contributed to the development of the American Society of Hematology’s guidelines for SCD and stem cell transplants, and I am a member of two working groups that are developing new gene therapy protocols for patients with the disease.

In December 2020, I established The Sickle Cell Reproductive Health Education Directive (SC RED) as a way to channel my frustration with the lack of reproductive health resources and costs associated with fertility preservation. There are over 250 SCD-related organizations in the United States, but ours is the first to focus solely on reproductive health. Our goals are to distribute a reproductive health curriculum to patients with SCD through their hematologists, OB-GYNs, and SCD care centers, establish support groups and mental health resources for those living with SCD, provide grants to help patients access fertility preservation technologies, advocate to make fertility preservation more accessible to patients, and sponsor research to close knowledge gaps surrounding SCD in the medical community. In less than a year, we have established an official partnership with Be The Match and recruited some of the country’s leading SCD clinical specialists, lawyers, ethicists, and industry partners to join our board and committees.

I am grateful to have found my purpose in life while facing serious health challenges. My advocacy work is my way of honoring my friends and others who have passed away due to SCD-related complications. I feel that sharing my story will help improve communication between patients and their doctors, which could improve their experiences and health outcomes. With groundbreaking research in progress, drugs in clinical studies, and important conversations drawing attention to our struggles, it’s a brand new day for those living with SCD. I am excited to play a role in what I think is a bright future for our community.

To learn more about The Sickle Cell Reproductive Health Education Directive, visit www.sicklecellred.org.