Rare Community Profiles is a Patient Worthy article series of long-form interviews featuring various stakeholders in the rare disease community, such as patients, their families, advocates, scientists, and more.

“We Have to Fight the System”: When Sierra’s Son Was Diagnosed with Warsaw-Breakage Syndrome (WABS), She Knew She Needed to Make a Difference

In just over one year, Sierra Phillips has made a splash in the rare disease community—and some days, she still can’t believe how much her life has changed.

Though she previously had experience in the human genetics and clinical trial world, with graduate training in human and molecular genetics, and working at a leading CRO as a program manager and business development liaison, she found herself thrust into the rare disease space after her fraternal twins, Charlotte and Jack, were born.

Months after Jack’s birth, and months into Sierra and her husband’s push for answers, Jack was diagnosed with an ultra-rare condition called Warsaw-Breakage syndrome (WABS). He was approximately the 20th diagnosed case in the world.

In learning how to advocate for Jack, Sierra has also become a fierce advocate for rare disease families across the board. In 2023, two years after Jack’s birth in 2021, Sierra launched the Warsaw-Breakage Syndrome Foundation, wrote the Rare Disease Resources Guide, and, alongside Albert and Flawnson of Comend, eventually translated these resources into Librarey.

By the end of 2023, Sierra also joined the team at GeneDx, a company with a mission to deliver personalized and actionable health insights to inform diagnosis, direct treatment, and improve drug discovery. With a laugh, she says:

“It’s been a whirlwind of 11 months.”

Of course, throughout her journey, Sierra and her family have also faced challenges: issues related to drug development, the impact of Jack’s rare disease on his sister Charlotte, and how to manage internalized and externalized pressure—including one person who, Sierra says, rudely messaged her on social media after the family chose to let Jack get cochlear implants:

“Someone sent me a DM saying that I mutilated him. In 10 years, he’ll be 12 years old and can decide if he likes them or doesn’t like them. But for now, as a parent, I’m trying my best. Rare disease parents struggle with how many big decisions we have to make and hoping that our children will understand. It can be challenging to hear that we’re not doing the best for our kids from people who don’t really recognize what we’re going through.”

Recently, Sierra sat down with Patient Worthy to discuss her family’s experience with Warsaw-Breakage syndrome, the power of community in rare disease, and the challenges and intricacies of working through the medical system.

Diagnosing Warsaw-Breakage Syndrome

Sierra was 16 weeks pregnant when an ultrasound revealed that Jack had a congenital heart defect known as an atrioventricular (AV) canal defect that is most commonly seen in people with Down syndrome. At first, the doctor recommended an amniocentesis to check Jack for any health conditions. However, Sierra and her husband decided against it. She shares:

“The ultrasound looked fine. I had also had many miscarriages before, so the 2% chance of miscarriage from the amniocentesis was too high for me. It was not a gamble I was willing to take. I wanted to know just as much, but I wanted to wait until they were born. Because they’re fraternal twins, I also knew that they were in separate placentas, so if something happened to Jack, it wouldn’t affect Charlotte.”

As her pregnancy progressed, weekly ultrasounds identified more concerning details about Jack’s health. He had poor placental blood flow. His severe growth restriction and microcephaly was diagnosed at 23 weeks.

The twins came into the world at 33 weeks. Jack weighed just 840 grams (1.85 pounds). Both Jack and Charlotte were quickly moved to the NICU, where Jack surprisingly did much better than Charlotte. He was the first to no longer need a feeding tube and didn’t really require surfactant for his lungs.

Jack and Charlotte spent six weeks in the NICU, during which time doctors performed a series of tests and health checks. Both a karyotype and microarray on Jack came back normal. When Sierra and her husband asked about whole exome sequencing, they were told that it wasn’t the right time for it—but the family could revisit down the road if they wanted.

For the next few months, Sierra and her husband did everything that they could to help their children thrive. And it seemed like both Jack and Charlotte were responding well—until one day when Jack woke up and refused to eat. Sierra shares:

“His automatic suck reflex turned off, which is how we ended up in inpatient care for a month. This is when I got him a G-tube. People thought I was crazy for wanting one because of the scarring, but I figured it wasn’t an issue since he had to do heart surgery anyways.”

By August 2021, Sierra finally convinced a doctor to do a whole exome sequencing on Jack. By the next month, the diagnosis came back as Warsaw-Breakage syndrome.

What is Warsaw-Breakage Syndrome (WABS)?

When Jack was diagnosed, doctors told the Phillips family that he was the 20th person worldwide diagnosed with this condition. The doctor had never heard of Warsaw-Breakage syndrome before and, despite her past experience in the clinic setting, neither did Sierra. However, she says:

“He was diagnosed early compared to others because I knew what to ask about; that’s what I went to graduate school for. My journey was different from many rare disease families because I pushed forward and could figure out a way to pay for whole exome sequencing. It really hurts me to think of families that can’t gain access because they don’t know what to ask or aren’t in the financial space to get the tests that they need. What I would tell people is to trust your gut. There’s only so much doctors can know and science changes quickly. There’s nothing wrong with asking for a second opinion. You know your kids more than anyone else and it’s hard to know when to push and when you’re at the mercy of the system. But if you see something in line with what you’re feeling, question that. Take the validation you need to go.”

Although Jack got diagnosed early, there was still little available information on Warsaw-Breakage syndrome. Although our understanding of WABS has slightly expanded, more research is crucial to understanding this condition.

Here’s what we do know:

- Warsaw-Breakage syndrome is an ultra-rare condition caused by DDX11 gene mutations. Normally, this gene provides instructions to make the ChlR1 enzyme, which plays a role in DNA replication and repair. The mutations cause DNA damage.

- An estimated 1 in every 1,000,000 people develop WABS.

- Signs or characteristics of WABS may include:

- Mild-to-severe intellectual disability

- Impaired growth which leads to a short stature and small head size (microcephaly)

- A small forehead, short nose, small lower jaw, and prominent cheeks

- Heart malformations

- Profound hearing loss

Sometimes, this profound hearing loss may take a few months to set in. Jack had a normal newborn hearing screen and passed a hearing test at two months. After reading all available papers on PubMed and learning about bilateral sensorineural hearing loss in Warsaw-Breakage syndrome, Sierra asked doctors to test Jack’s hearing again. At this point, she says:

“He was flatline, profoundly deaf. We were able to speed that process up and get him cochlear implants before age two. Many other children with WABS don’t have cochlear implants because they were diagnosed too late, or doctors and parents didn’t know what to look for. We still sign to Jack, but he can hear too. He’s babbled and made vocalizations, and in December, he said ‘mama’ for the first time. That’s a great show of why early detection and testing are so crucial.”

Finding Community

As Sierra began preparing for Jack’s heart repair surgery in January 2022, she also fervently searched social media for others who understood her experience. But there was no strong community for Warsaw-Breakage syndrome. At the same time, she knew that there must be others out there who knew what she was going through. So she began adding the hashtag #WarsawBreakageSyndrome to every post she made.

Eventually, another mom connected with her. They created a Facebook group and are working on incorporating the Warsaw-Breakage Syndrome Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the lives of individuals and families affected by WABS. The foundation aims to empower and support patients by providing research, advocacy, and community engagement—and to advance research towards finding a cure. Says Sierra:

“Don’t underestimate the value of community. There may not be a treatment and it may not change medical management, but finding community can help bring you comfort and support.”

In February 2023, Jack required another heart surgery. Finally, Sierra felt like her son was in a place where his health was stable. At that point, she started thinking: what else did she want to do? How else could she get involved?

By March and April, Sierra had introduced her Rare Disease Resource Guide to social media; it took off like wildfire. The guide was over 200 pages long and delineated into sections based on areas like disease state or geographical location. Soon after, Sierra began visiting rare disease conferences and creating a broader community. She shares:

“I love helping people. It’s what energizes me. I want to help people avoid the mistakes that I made. Doing this gives me something to do with my anxious energy and helps me feel like I’m doing something good for other people.”

In October 2023, Sierra and her business partners Albert Wang and Flawnson Tong launched Librarey, where rare disease families can find and share resources. The idea flourished from Sierra’s understanding that the best resources and tips come from other families, caregivers, and patients in the rare disease space. To Sierra, Librarey represents her calling to empower the rare community and her desire to give back. But she also wants to remind others that they don’t necessarily have to follow the same path:

“Everyone has something they will be called to do at some point; this is mine. If you haven’t found your calling yet, that doesn’t mean something is wrong with you. It’s hard to compare yourself to others in the spotlight. You’ll find something that you’re passionate about. If you haven’t started a foundation or consultancy or startup, it’s okay. You don’t have to do something major. Even little things are important. And there might also be times when you can’t do something. I’ve had to step away when Jack is dealing with health issues or hospitalizations. The biggest thing I’ve wrestled with was not comparing myself to others and hearing negative comments, but I want to remind you to try not to internalize them.”

Dealing with the Pressure

As Sierra explains, the rare disease community faces a significant amount of pressure and feedback, especially given the prevalence of social media:

“The constant feedback and internalized perception of pressure, and external pressure, can be hard to manage. With social media, certain things ‘trend.’ Heat on rare disease parents has been high and volatile: we’re ableist, exploiting our kids, and sharing their stories without consent.’ Someone’s kid may never be able to give legal consent for themselves, so what does that mean? We’re just doing the best that we can and trying to do the best for our kids. I laud social media for connecting the rare community and connecting my family with the other WABS families across the world, but there’s a double-edged sword of negative feedback when you put that out there in a public way.”

But the pressure to perform as a perfect parent can also be challenging and overwhelming. It’s important to remember, first, that perfection isn’t possible; if you’re a parent, and especially a rare disease parent, you often find yourself grappling with ideas or questions you never knew you’d face. For Sierra, the medication and appointment management can be challenging, as can making decisions about putting Jack into a deaf/HoH classroom or not, or finalizing an IEP. But one of the largest challenges that rare disease families face, she says, is the impact of a child’s rare disease on his or her siblings:

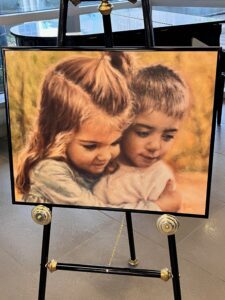

“The sibling part really eats me up. I hope Charlotte looks back and recognizes why I’m doing this and why I have to spend more time with Jack. There’s a lot of pressure and expectations from society on how to raise children, and I hold a lot of internal pressure too. But it’s hard. There are certain things you have to triage. Sometimes I have to say, ‘Your brother is actively puking/seizing and I can’t get you fruit snacks right now.’ You learn as you go, but it’s so hard. Charlotte is so sweet though. Back in September, we noticed that Jack was having seizures, and we needed an emergency EEG. Charlotte came waddling in and said, ‘Jack Jack ok?” I said yes and she followed up with, ‘You ok? Mama, I love you.’ She’s so intuitive and empathetic—but that also makes me hypersensitive to making the right choices and acknowledging her experience as his twin sister.”

Coming Together for Change

Despite the challenges and pressure that come from both internal and external expectations, Sierra continues to steadfastly work towards change through her work. She notes that, at times, the rare disease community can be competitive or conflicting. But, she says, to make a difference, it’s necessary for groups to come together in unity and solidarity:

“We have to fight the system and not each other. We all want different things, but we work better together. Sometimes there are multiple organizations in the same space, but don’t make decisions that will harm the community as a whole. My work has this same ethos in mind with neutrality and no gatekeeping. I want people to have all of the information to make the best decisions for themselves.”

Through GeneDx, Sierra and her team are working to streamline the diagnostic process and shorten the diagnostic odyssey. She is currently working on implementing provider and patient education and re-education on why whole exome and whole genome sequencing should be the lead on testing. Additionally, the organization recently started a patient advocacy and engagement section led by Gay Grossman to give back to communities. Says Sierra:

“We want to make sure that we’re walking the walk and talking the talk to do what’s best for patients.”

Outside of connecting the community, the WABS Foundation is also searching for ways to advance research and drug development. Sierra shares:

“It’s hard to think that drug developers aren’t interested in WABS because it isn’t profitable. But I also understand that these organizations have to start somewhere first to have a profit, and that my lens is slightly different because WABS is not neurodegenerative and we’re not in a race against the clock. My mindset is that we have to pave the road and start somewhere, and using some of the bigger and more common indications as starting points is what will make rare diseases attractive and profitable. You can pick an indication that won’t be the breadwinner but gives you the runway to dabble. I would love to welcome others into this space, and I’m looking for groups where we could complement each other.”

If you are a research organization, nonprofit, or biotechnology/biopharmaceutical company who would like to get in touch with Sierra and the WABS Foundation to discuss research or drug development, you may reach her at [email protected]