I have Gaucher disease.

I often wonder what it would be like to not have this disease. But then I stop and redirect my thoughts. I’ve spent too much time in the past wishing I weren’t born with Gaucher. Instead I shoot for the stars and think about how to make change. We need to find a cure for this disease.

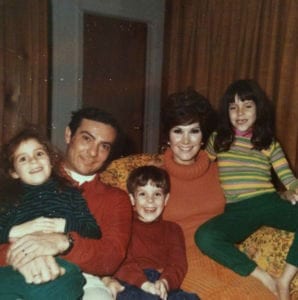

I was diagnosed with Gaucher in 1976 when I was 13 years old. It was a long time ago, I’m 55 now, but every day I have reminders that I have a rare genetic disease. Like so many others with rare diseases, it took years to be diagnosed and most of the symptoms were ignored. But when I was 12, I had a huge bruise on my calf that demanded attention. It wasn’t my first bruise, I had a lifetime of bruises and bloody noses, debilitating fatigue and bone pain, a low immune system and high fevers, but pinpointing a cause for these symptoms didn’t seem important at the time. The bruise finally caused worry though, and forced our pediatrician to come up with answers.

I was first misdiagnosed with malnutrition and told to eat red meat and sit in the sun, but when the bruise got worse over time, a blood draw pointed to a low red blood cell count and high white count. I was misdiagnosed with leukemia and sent to a brilliant hematologist. After a year of blood draws and visits to the hospital twice a week, in a pre internet world where researching information meant hitting the books and talking to others, my doctor found Gaucher. Bone marrow was taken from my spine and put under a microscope. And there it was. I have type 1 Gaucher.

Type 1 Gaucher is the most common genetic disease affecting the Ashkenazi Jewish population. I am Jewish on my father’s side, one quarter Ashkenazi and one quarter Sephardic. Part of what made the doctors question whether I was a candidate for Gaucher though was my non-Jewish mother, partly of Swedish decent. But what they weren’t aware of then, is that there is an area in northern-most Sweden called Norrbotten, where my great grandmother came from as did a unique mutation of type 3 Gaucher disease. The type 1 gene mutation from my Ashkenazi grandfather on my father’s side and the type 3 gene mutation from my Norbottnian Swedish great grandmother on my mother’s side were both passed down to me.

Gaucher disease is an autosomal recessive genetic disease, which means that two gene mutations are necessary to have the disease. It also means that I am lacking an enzyme, and without the full amount of the enzyme, I can’t break down a certain lipid or sugary fat that is normally in the body. You build yours up and break it down with the enzyme. I build mine up but I can’t break it all down, so it accumulates in certain organs, namely the bones, liver, spleen, lungs and in more rare type 2 and 3 cases the brain. Gaucher manifests differently in every single person, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe and early death. Type 1 disease is non-neuronopathic, it doesn’t affect the brain, but types 2 and 3 Gaucher, which are not predisposed to any ethnic population, are neuronopathic, and they affect the central nervous system, including the brain. Type 2 babies suffer from life-threatening medical problems beginning in infancy and usually don’t live past 18 months; type 3 disease also affects the nervous system but symptoms worsen more slowly, allowing their life span to last into the 20s and 30s and sometimes longer.

Although I am lucky to have type 1, regardless of disease or severity, thirteen is an impressionable and difficult age to be diagnosed with a genetic disease. I had braces, was skinny and pale, and I was incredibly awkward at that age. It left me feeling self-conscious and self-loathing, and when I was diagnosed I went into a tailspin. It made me feel dirty, and I couldn’t shower enough to get rid of the disease. It was in my blood and would always be there. Because there was no treatment, I was told there wasn’t much we could do; my bones would disintegrate and I would be using a wheel chair by the time I was 20, and I most likely wouldn’t live past 30.

My health continued to decline throughout my teens and 20s. The fatigue was so extreme I couldn’t get out of bed, and the bone pain was so severe I couldn’t walk up a flight of stairs. I looked pregnant from all the Gaucher cells caught in my spleen, and my skin and eyes were yellow from the cells caught in my liver. My spleen grew to 9 kilos, over 20 pounds, and I was in pain. But what wasn’t visible and affected me even more than the physical pain was the depression and emotional stress that settled upon my heart.

As my symptoms worsened, I went further and further into denial about my disease. I told no one, I spoke to no one, I ignored that I was getting sick. I felt isolated and alone. I became hopeless and suicidal. It is difficult to stay positive with chronic pain and no hope, but I knew I had to change my life around. I couldn’t live like this anymore.

When I was 25, I learned of a drug trial at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that could possibly help this disease, but I was too sick to participate in the trial. Instead, I had one of the first successful partial splenectomies and 19 pounds of my 20-pound spleen were removed. After a tough healing period, my life almost changed overnight. I felt great – I had more energy, less pain, and I started talking about my disease to anyone who would listen. Therapists, friends, strangers, it didn’t matter, and I started to shed decades of bad feelings that surrounded my heart. Emotionally I was healing.

An extension of the drug trial at the NIH opened, and I was quickly enrolled and started receiving the first enzyme replacement therapy ever to be administered. It worked really well. While I was in the trial, the FDA approved the drug in 1991, and people with type 1 Gaucher had a chance. For the first time I realized I had a future without daily pain and sickness. Physically I was healing!

Treatment for the type 1 Gaucher community has been a godsend. Since its first approval, I have seen friends at patient meetings transform from sickly people with large bellies, pallid skin, crutches, and wheelchairs to healthy, vibrant, smiling people. They have a quality of life beyond what any of us ever imagined. They work, raise families, and contribute to society like most other healthy people. Younger people born with Gaucher now go on treatment as soon as they are diagnosed. If it is early enough, they will never experience the pain and suffering people from older generations experience. They will lead completely normal lives. It is a dream come true. But there is still so much more that needs to be done. And until we have viable treatments that cross the blood-brain-barrier for types 2 and 3, we cannot get too comfortable.

Now that I was feeling better, and being my mother’s daughter, I realized I had to give back and help the community where I received so much help over the years. How can a patient like me help? I decided to participate in every drug trial I could, knowing that being involved may help to bring more treatments and more options to market and bring down the cost of drug. And if the cost of drug comes down, there may be better access to patients all over the world.

What else? I began to get more involved in the Gaucher community by speaking at meetings and conferences to raise awareness of Gaucher and share my patient experience. With more education, doctors and nurses can help better identify and diagnose a rare disease like Gaucher. And with awareness, more students, specialists, and researchers will take an interest in Gaucher and find more funding to specialize in this disease and find more treatments and possibly a cure.

At 40, when I realized I would not have children, I knew there had to be more. I worked for the National Gaucher Foundation for over a decade, helping to raise funds for Gaucher and create better advocacy for the patients and their families. I met hundreds of Gaucher families, all on their own path figuring out how to cope both physically and emotionally with this disease. Meeting these families changed me forever. I have made some of the best friends in this community I will ever have. They are the reason I find strength to carry on.

These are all such small things, but it is my way to have a voice. Each and every one of us has a voice with this disease, and we need to stand together to have a louder voice. And then I realize I’m not the only one doing this. So much has been done by so many amazing, generous, and passionate people within this small but incredibly strong and cohesive community. Together we are one, and we support one another from the bottom of our hearts.

And now, as I look back on my personal journey with Gaucher disease, I don’t regret a second of having this disease. Yes, I have Gaucher disease. This horrible disease has brought goodness to my life.

Today is International Gaucher Day. Today is for every single person out there who is affected by this disease. Together we can have a voice – patients, family members, friends, researchers, doctors and drug developers – to make change for this disease. In a perfect world, we would not have disease. But if we had to have disease, I hope we can find a cure for every single one of the 7,000 rare diseases that exist. No one would suffer. No one would be sad. It would be a perfect world.

Cyndi is a patient advocate and a long-standing member of several Gaucher and rare disease communities. Over a 40-year span, she has participated in many clinical trials and research studies to help bring treatments to market. After working for the National Gaucher Foundation for nearly 11 years as a fundraiser and patient advocate and with biotech in patient advocacy, she continues to act as a mentor and advocate for Gaucher patients in the community and raise awareness through speaking at patient educational events and conferences, Gaucher and rare disease symposiums and pharmaceutical patient and educational meetings. She has served on multiple boards and committees for many rare disease organizations, including Global Genes Advocacy Leaders Group, Corporate Alliance Committee and Patient Education Committee; the National Gaucher Foundation’s Gaucher Advisory Group and as a patient advisor to Sanofi Genzyme, Shire, Pfizer and Blue Turtle Bio.

Cyndi was diagnosed with type 1 Gaucher disease in 1976 at age 13 before treatment was available. Part of her passion for helping rare disease causes stems from her personal experience with Gaucher and having to learn to cope with a progressive illness during her teenage years and into her 20s. When symptoms associated with Gaucher disease nearly took her life, she realized that instead of using the illness as an excuse not to get involved, she must use it as the reason to get involved and help others who might be struggling as she was. Cyndi’s belief is that education is an incredibly powerful tool, and through educational and support programs we can help provide these tools to others who may otherwise be struggling with their disease.

Share your thoughts and your hopes with the Patient Worthy community!