Patient Worthy has the distinct pleasure of attending the Sixth Annual Rare Disease Genomics Symposium at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) this weekend. Today, we heard from lead researchers about their efforts in genetics to achieve better outcomes for patients and families.

Alabama Genomic Health Initiative (AGHI) – Affected Cohort

Bruce Korf, MD, PhD and UAB’s Chief Genomics Officer kicked us off, introducing Anna C. E. Hurst, MD, MS who spoke on the Alabama Genomic Health Initiative (AGHI) – Affected Cohort. Dr. Hurst educated us on the process of whole genome sequencing and the role it plays in diagnosing rare diseases. For this program, patients are typically referred to AGHI by a physician who submits the form online, explaining who the patient is, the physician’s medical concerns, what previous genetic testing has shown in the past, and what their team is looking for in doing whole genome sequencing. The AGHI then decides if the candidate is appropriate for whole genome sequencing (must be an Alabama citizen).

They have deferred some patients, in part because there is a waitlist, the candidate needs more tests done, or the candidate needs to see a genecist first. In a lot of these cases, the deferred patient could eventually get whole genome sequencing done. The wait time for whole genome sequencing in accepted cases is only three to four months.

In short, this program is helping in the diagnosis journey for patients who have suspected genetic disorders, and whole genome sequencing is becoming increasingly important in patient and family outcomes.

We then jumped in to population genetic testing across Alabama, presented by Kelly East, MS, CGC.

Statewide Population Screening Initiative for Genetic Health Risk

Why is it important that we test the general population? Not only is genetic testing getting cheaper, but we’re also starting to understand gene changes and their impact on disease risk. With this improvement in understanding, there is a growing concern around the fact that people are unknowingly walking around with high risk of developing a disease. Genetic testing is also useful in cases where family history is unknown due to adoption, poor communication, etc.

The AGHI Population Cohort offers to adults 18 or older and living in Alabama, enrollment to receive testing by Illumina Global Screening Array. The AGHI is reporting back pathogenic and likely pathogenic changes in genes as indicated by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) gene list. For those unfamiliar, ACMG put out a list of 59 genes that are important to observe and report back on because they’re impactful, disease risks are high, and there is action we are able to take on these genes.

The process for this program starts with enrollment, sometimes by way of luck (e.g. a potential participant walking past a recruitment table). The participant signs an informed consent and fortunately, there is no cost to the candidate. The participant’s blood sample is collected and tested, and then the candidate receives the results.

Of the population right now, 74% are women so they’d like to increase their engagement with men. All but one county in Alabama have been covered in this study. Ninety-one percent of participants have consented to their results being stored in a biobank, but only 47% have consented to having their results sent to a provider of their choice. This latter low result is likely due to participants not having primary healthcare providers or not knowing their provider’s information on hand.

Fifty-seven of the 4231 participants have had actionable results returned to them (or ~1.4% of the population). Those participants who actually got actionable results received a call from a study genetic counselor and a result letter with specific and individualized information. So far, tumor and cardiac risk genes have been the majority of results found of the 1.4%. Two thirds of this population had flagged family history, but about half of those actually flagged their family history for something irrelevant to the results found by AGHI.

This statewide population screening initiative is currently working on a survey to find out how the population is using the results, i.e. if they talked to their doctors, family members, increased testing across their families, etc. to see if genetic testing has impacted their care and their families’ care.

SouthSeq: Genomic Diagnosis for Ill Newborns Across the South

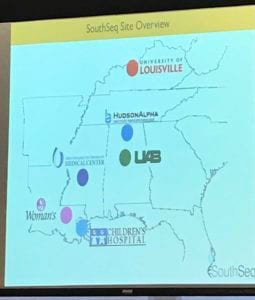

Next, we heard from Greg Cooper, PhD on SouthSeq: Genomic Diagnosis for Ill Newborns Across the South. Specifically, he discussed the HudsonAlpha Pediatric Genomic CSER Project. This effort started in 2013 and includes collaboration with Dr. Martina Bebin, a UAB Neurologist, and North Alabama Children’s Specialists in Huntsville, AL.

They recruited 500 families dealing with intellectual or developmental disabilities, who were in need of a specific diagnosis. They then conducted genome sequencing on these families to identify causal genetic variants, returned those results to the families, and then evaluated the impact of genetic information results return on the families’ health and well-being.

Researchers looked at 581 probands in 532 familiar and 1500 individuals, including parents. Twenty-one percent had a pathogenic variant. These typically lead to a diagnosable condition, for example Dravet Syndrome or Rett Syndrome.

One challenge in rare disease is even if you sequence a huge cohort, extremely rare disorders aren’t likely to manifest more than one or two times. So, matching patients in sequencing centers across the world with rare genotypes/phenotypes is necessary to really uncover new genetic disorders. GeneMatcher is a tool that can help with matching. As Dr. Cooper put it, it’s like Cragislit for rare disease geneticists.

Dr. Cooper then touched on the increasing importance of re-analysis, especially in cases of rare disease with severe phenotypes. Re-analysis is critical not only at variant and gene-levels, but at the patient level. For this project, researchers may treat an old case like a new one every 24 months, to see if anything new is found in that patient. Through this practice, 15% of original cases who were not given a pathogenic result, ended up with a pathogenic result.

Some key conclusions from this project are:

- There is a high need for more genetic counselors.

- Sequencing is effective in diagnosing and researching pediatric and neurodevelopmental disease. The value of this is significant especially in diagnosing a young children versus adults.

- Rapid improvements in sequencing, analytical tools and data sharing, are improving the diagnostic yield.

- They need to reach new and more diverse populations to improve clinical impact, among other reasons.

The SouthSeq program, which is part of CSER, aims to perform genomic sequencing in 1500 infants in NICUs with symptoms that prompt a genetic referral. They will work with hospitals that are rural, contain medically underserved populations, and/or have more African-American candidates.

Stakeholder engagement is key for this effort, so they will work to gather input from representatives of various groups impacted by SouthSeq, including parents of children with congenital disease, physicians, rare disease advocates, hospitals and insurance administrators, and community leaders. Engagement efforts will include test surveys, “town hall” style meetings, and more, to collect feedback and readjust accordingly.

Enrollment starts with a NICU nurse, then genome sequencing and analysis will take place at HudsonAlpha, then half of the participants will go in the standard arm with a genetic counselor to discuss results. The other half will get results from a NICU provider. The NICU providers are being trained to do this in a safe and effective way, since typically a genetic counselor is involved in this process. Of course, genetic counselors will review the results for any potential errors and associated safety risks.

The outcome scale will try to look at results directed toward family empowerment, how the family understands the results, and whether or not they feel the information is useful. But the team also wants to see if the NICU provider is as effective as a genetic counselor in delivering the results, so that we can expand options for those working with families with genetic variants.

Right now, this project has 238 individuals. The clinical trial is set to begin by April of this year. Currently, diversity has increased with about 50% of enrollment consisting of minorities. So far, they’re seeing similar results to the first study, with about a quarter having a positive variant that could lead to a diagnosis. Those who have a likely diagnostic result, have rare indications such as CHARGE syndrome.

Dr. Greg Cooper closed out with a case study on a 4-day old female. She came back negative for suspected conditions, including what the physician initially thought was manifestation of Myasthenia Gravis. The patient did get a variant in CHAT, associated with Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome which does align to the physician’s initial intuition, though is slightly different than MG. Thus, the genetic results did inform the physician’s treatment of the infant.

All of Us Research Program

We next heard from our esteemed moderator and Chief Genomics Officer of UAB Dr. Bruce Korf, on the All of Us Research Program. In short, this is an effort from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to gather data from United States citizens, 18 or older, to inform delivery of precision medicine. The goal is to rapidly advance health research and medical breakthroughs, through the development in individualized prevention, treatment, and care. While participants may share their samples and data, their data and personally identifiable information is protected. Researchers will then study the data to find patterns, and the participants will eventually get results from their data, hopefully informing them to learn more about their own health. Overall, the data should inform the development of individualized care. To find out more about joining this effort, click here.

Parent and Patient Impacts of Genetic Testing

We wrapped up the first half of the day hearing from the families who received diagnoses and how that changed their lives. One family spoke about how during pregnancy, the mother did not have any results indicating a disorder, and noted that the pregnancy was remarkably easy. The first couple of days after childbirth however, was very overwhelming. After a year of many surgeries and hospital visits, the family received a diagnosis. Her son is one in sixteen with an ultra-rare disease, and she expressed gratitude for what she considers a quick diagnosis, given the incredible complexity of his condition.

The family is also grateful to know the specifics because they now know what the prognosis means, and how it affects the future children in their family. While there is still much to learn about the rare disease, this family has hope that the more common testing becomes, the more information will be available to the public.

Another family member spoke who was enrolled in the SouthSeq program. Their daughter spent quite a few months in the NICU right after birth, but 90 days after they took one vile of blood, she received a diagnosis and swift treatment. While there are a lot of therapies, specialists, and doctor’s visits, this family member feels there is great progress since the rare diagnosis and appropriate treatment response.

We also heard from an adult woman patient who already knew she had pulmonary sarcoidosis and ankylosing spondylitis, enrolled in the aforementioned AGHI Population Cohort. Her family history was such that everyone lived until they were very old. She signed up for the AGHI Population Cohort with her husband “for fun” and while he got a letter of results, she eventually got a phone call with her results. While she has no heart history in her family, it surprisingly turned out she had a cardiac gene variant. After this discovery, she went to her cardiologist thinking she had cardiac sarcoidosis, but she was negative for this. She called her siblings and let them know about the cardiac variant, and they said they didn’t want to get genetic testing. Her cardiologist suggested that this patient’s adult daughter get tested for a gene variant, who has yet to be tested as well due to scheduling issues. For now, this patient still has fatigue as a result of her sarcoidosis and her main goals are to walk 10,000 steps per day, climb stairs and walking her dog.

Genetic testing, specifically whole genome sequencing, has been a hot topic in the rare disease world for years. But after hearing about the practical application of this across rare families and the general population in Alabama, it provides hope that this is becoming an increasingly common effort throughout the United States as whole. The south has long needed more attention toward rare disorders, and UAB is at the forefront of filling that void.

As a rare disease patient myself, I am grateful for their programs to advance breakthroughs in diagnostics, treatment and care. Stay tuned for our live coverage of the Alabama Rare Disease 2019 Patient/Caregiver Symposium tomorrow!