Alex Biagi was planning to try out for his high schools basketball team, and could already dunk. He said his dream was to be a professional basketball player. He grew up in an artistic family, and had played piano almost every day since age 6. He also did soccer and martial arts, an all around athlete. Drawing had been a permanent facet of his life, and since he was young he assumed he’d be a cartoonist or something in the art world.

When he was injured playing basketball in high school one day, he was surprised to find it escalate into severe cramps and shocks, winding him up in the Children’s Hospital in Denver. Doctors couldn’t explain the extreme pain he was experiencing. Here began his health journey. After going through hoops and barriers to prove the pain was real and severe, he finally got an MRI. They diagnosed him with spinal stenosis, a disease nobody had suspected because it usually only affects people over 50. The disease means the spinal canal is narrowed causing pressure on the sciatic nerve, necessitating the removal of part of his vertebrate. He had to relearn to walk, and spend the rest of the year home schooled. He got physical therapy and had four more knee surgeries over high school, so he couldn’t jump back into playing sports competitively.

He played basketball until he couldn’t anymore. He wrote,

“You’re probably asking yourself, why would I still continue to play basketball with all of the things that happened to me? Well, when you love something you do it until you can no longer do it.”

Still, sports are a fervent passion that he can engage with in any health state in one way or anything. As a lifelong Denver Nuggets fan, he said, “I’ve almost seen every Nuggets game for last 16 years, but I’ve been a diehard since 1989.”

Instead, he dove into art and music. In 2000, he went to college for 3D animation, multimedia production and design, and found his way into a double major in music. He began to invest in more music equipment to produce electronic music. He wrote, “I figured since I wasn’t going to pursue sports this would be the next best thing and things were going great,” he continued, “And I was starting to feel really good!” He was just finishing up school when, he wrote, he “came up two classes short before the disease started.”

The Onset

Alex began to experience cramps that were severely painful, enough to have him writhing on the floor in pain mid-work day. He wrote, “It turned out the discs between the vertebrae were starting to deteriorate in my lower back due to the previous surgery. More spinal surgery was in store for me, this time to stabilize my spine.” He went through another phase of pain and surgeries, until three years later, he began to have cramps and numbness in his hands. He explained, “It started in my left hand, I couldn’t spread my ring finger apart. It just started out of the blue one day and spread up to my elbow. It was like when you hit your funny bone, it felt like that all the time.” He was initially diagnosed with carpel tunnel syndrome and given surgery for it, but his cramps only got worse, spreading to his legs and feet. They realized they weren’t getting it right. So they sent him to the Mayo Clinic in Arizona in March of 2008. Here, he got his answer.

His Diagnosis

When Alex was 27, he was diagnosed with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy or CIDP, a rare disorder that affects the peripheral nervous system, causing inflammation in the nerve roots, destroying myelin sheath and nerve fibers. This slows nerve signal communication. This autoimmune disorder causes difficulty walking or using arms and hands, different sensations such as numbness, pain, burning, or tingling, uncoordinated movement, fatigue, difficulty breathing, and voice changes.

While had been immobilized for years by the symptoms, he had been plagued by not only the disease but misdiagnosis and resultant incorrect surgeries. He was finally diagnosed by the Mayo Clinic in 2008. He said, “they were able to diagnose me after three days, after four years of not knowing, after the misdiagnosis.”

Finding New Ways to do his Passions

His disease was eating up his ability to continue his passions in the ways he’d done them before, but he was finding new ways to express them. He watches basketball religiously, a hardcore fan of the Broncos and Denver Nuggets. After his hands were paralyzed, he had luckily maintained use of his right index finger, so he could use a computer mouse to continue to make music. Painting had become inaccessible when his hands became paralyzed, but he explained,

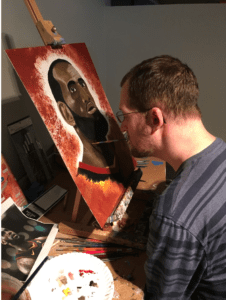

“One day, my mom showed me a catalogue of mouth and foot artists, MFPA, and they put out a calendar of mouth and foot painters. So five years ago, I started painting. I’m actually trying to get into that organization, I’m sending my art when the quarantine is lifted.”

Coming Back to Art

So he created a set up in a corner of his home, with a desk and a small easel with his paints, working on canvases that are about 15×20. Not only did he need to funnel creativity into his work but into his unique method. When it came to developing technique, he was his own teacher. He explained, “I just kind of did it myself and developed my own way of doing it and how to rotate the brush. It was trial and error. Like anything, it was just practice and more practice.”

As a lifelong artist though, he said his style ultimately didn’t change much. He said, “I try to go for realism or as close to realism as I can get.” Really he just developed a new way of expressing himself. He explained, “Its like riding a bike. You get back into it; you figure it out again.” Painting with your mouth is notably more tiring, so it takes him more time to create each piece, about a month and a half to three months. He said he’s worked up to being able to paint for an hour at a time, but his jaw gets tired out and begins to spasms. He said, “Thats the hardest part- neck strain, building up your muscles. My condition causes muscle wastage.”

He said his most unique work was commissioned by his neighbor to do her german shepherd, Aero. Alex displayed this at the art gallery at Rare Disease Week 2020 on Capitol Hill, where he spoke in front of 200 people in February. He had never spoken in front of a large group like that before, and it was a testament to how far he has come. Before he got a stem cell transplant, the first ever in Colorado, he had been in a power chair for four years. He said, “When I was in DC, I walked 4 miles, the longest I’ve walked in 16 years.”

To see more of Alex’s work and read his story, visit www.alexbiagi.com and follow him on Instagram @alexbiagi680