Since the dawn of time, the human body has changed to cope with microbes and environmental changes. As a result, specific gene mutations evolved to protect populations from harm. Some Mediterranean populations are predisposed to familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) based on MEFV gene mutations. However, researchers believe these same mutations have evolutionary value and may allow for resistance against Yersinia pestis, the microbe causing the bubonic plague. Check out the full findings in Nature Immunology.

Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF)

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an inherited condition causing painful joint, lung, and abdominal inflammation. Resulting from MEFV gene mutations, FMF generally occurs in people of Mediterranean origin, including Greeks, Italians, Turks, and Sephardic Jews. Around 10% of people in these groups have at least one MEFV gene variant. However, FMF requires 2 genetic mutations.

Normally, the MEFV gene instructs the body to create pyrin, a protein in white blood cells. Pyrin, in turn, regulates inflammation and immune response. However, for patients with FMF, their pyrin is abnormal. As a result, it can suddenly activate, leading to fevers and inflammation. When these “attacks” occur, patients may experience the following symptoms for 1-3 days:

- Joint swelling and pain

- Fever

- Muscle aches

- Abdominal and scrotal pain

- Red rash on the lower extremities

- Arthritis

- Renal failure

Learn more about FMF here.

Research

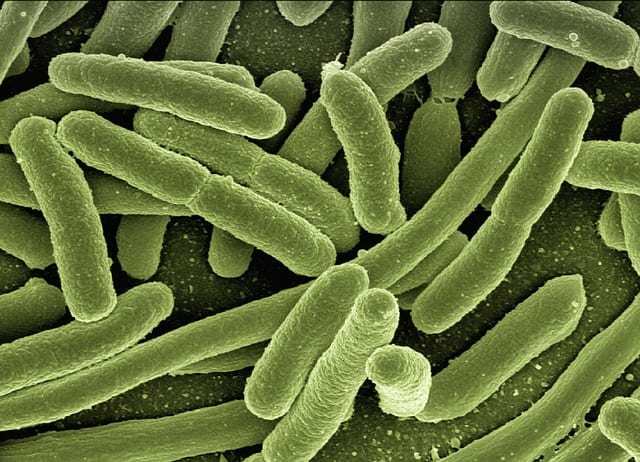

According to Dr. Jae Jin Chae, PhD, researchers believed that MEFV gene mutations may have been evolutionary beneficial. So, to begin, researchers examined Yersinia pestis. They discovered that one of the microbe’s molecules prevents pyrin from functioning properly. Because of this, the body’s immune system fails to fight against the invading plague.

Since people with FMF have mutated or abnormal pyrin, researchers then hypothesized that MEFV variants were designed to protect against Yersinia pestis.

But why would the body “willingly” get one disease? Well, while the bubonic plague has a 66% mortality rate, under 1% of the population has FMF. Therefore, FMF is the “safer” option, biologically speaking.

Next, researchers analyzed the genetics of 2,313 Turkish individuals, as well as 352 ancient archaeological samples. They discovered that FMF-related gene mutations rose in frequency around the Justinian Plague and Black Death, marking these mutations as positive gene selection.

Then, researchers sourced white blood cell samples from patients with FMF and those with only one genetic mutation. Yersinia pestis failed to lower inflammation in these cells, whereas it did in healthy patients. Researchers hypothesized that, if infected by Yersinia pestis, those with these mutations are more likely to survive.

Finally, researchers infected mice models of FMF with Yersinia pestis. Compared to healthy (but also infected) mice, the mice models of FMF had better outcomes and lower mortality. As a result, researchers concluded that the genetic mutations associated with familial Mediterranean fever were positively selected to protect people from the bubonic plague and other Yersinia pestis-related illnesses.

Read the source article here.