Rare Community Profiles is a Patient Worthy article series of long-form interviews featuring various stakeholders in the rare disease community, such as patients, their families, advocates, scientists, and more.

A Potential Turning Point for ALK-Positive NSCLC: Dr. Ken Culver Shares Insights from the Phase 3 ALINA Study on Alecensa

During the ESMO Congress 2023, held in October 2023, researchers and stakeholders across the medical realm came together to discuss innumerable topics in translational cancer science. Conversations spanned from the clinical perspective on cancer biology and diagnostics to the latest breakthroughs in basic science, translational, and clinical cancer research.

The results of the Phase 3 ALINA clinical study, which evaluated Alecensa (alectinib) for early-stage ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), were shared at the Congress’ Presidential Symposium. Alecensa was found to significantly improve disease-free survival (DFS) and reduce the rates of both recurrence and mortality in early-stage ALK-positive NSCLC.

Patient Worthy sat down with Dr. Ken Culver, the Director of Research & Clinical Affairs for ALK Positive, Inc., to discuss what these results mean for people living with ALK-positive NSCLC and how Alecensa, if approved, could transform the treatment landscape.

What is ALK-Positive Lung Cancer?

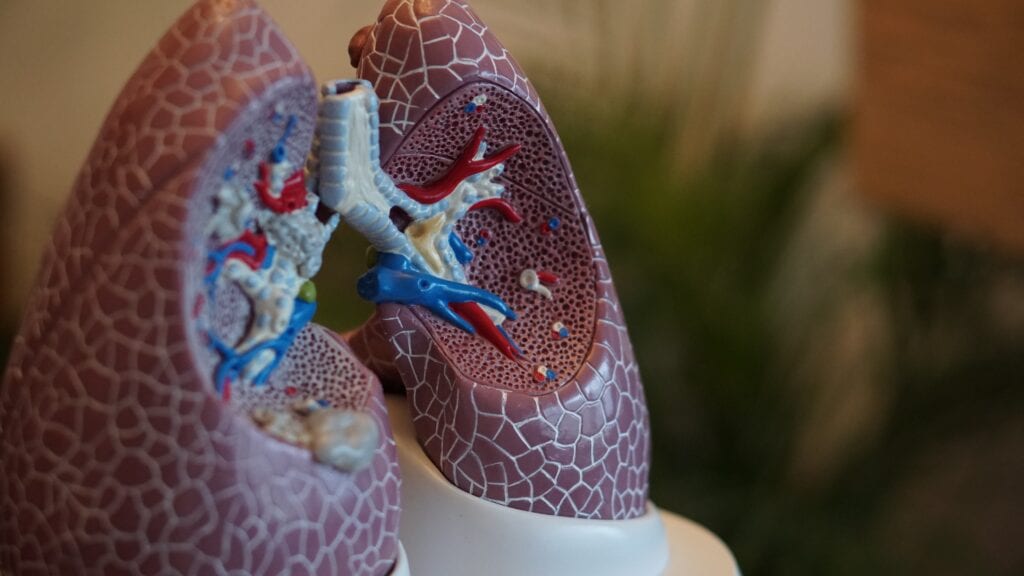

Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Positive (ALK-positive) lung cancer is a form of lung cancer that occurs due to a rearrangement of the EML4 and ALK genes, leading to a new EML4-ALK oncogene. ALK-positive lung cancer comprises about 5% of all lung cancer diagnoses. However, shares ALK Positive:

“It occurs in approximately 30% of lung cancer patients diagnosed under age 40. About half of ALK-positive lung cancer patients are diagnosed before age 50 (compared to about age 70 for lung cancer overall), with many in their 30s and 40s, but some even in their teens and twenties.”

Symptoms of ALK-positive lung cancer may include shortness of breath, fatigue or general weakness, coughing up blood, wheezing, a persistent cough, chest pain that worsens when breathing or laughing, appetite loss, weight loss without trying, and hoarseness.

One of the challenges around diagnosing ALK-positive lung cancer is that many doctors do not test every newly diagnosed lung cancer patient for ALK rearrangement. Says Dr. Culver:

“There’s a stigma around lung cancer that you develop lung cancer if you’re a smoker. In ALK-positive lung cancer, it is uncommon for anybody to be a prior smoker. The proportion of people who get lung cancer but never smoked is going up. That in itself presents two problems: the lack of awareness but also a societal question of what in our environment people are vulnerable to. If more women are dying of lung cancer than of breast cancer, and the number of lung cancer cases attributed to smoking is going down, there has to be an environmental aspect. The other conflict is that doctors are just not testing every patient with lung cancer for genetic underpinnings. EGFR and ALK make up a significant amount of lung cancer diagnoses. So why testing occurs in only about 60% of new lung cancer patients, when people can live for years with the proper treatment is not clear to me. We need a new approach to solving this inadequate testing problem because it is tragic. The data from ALINA makes this even a bigger issue, since Alecensa in these early stages may be curative. Without testing patients will not get the opportunity to benefit!”

Despite these challenges, the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatments targeting the ALK gene have increased survival rates to about seven years. Earlier diagnosis and treatments directed at early-stage ALK-positive lung cancer could further improve survival.

Pushing for Cancer Research

Dr. Ken Culver is a physician by training with a specialty in immunology. His career has encompassed numerous medical advances. While working at the NIH, he administered the first gene therapy treatment for adenosine deaminase deficiency in 1990 with Mike Blaese and French Anderson, before migrating into cancer research at Novartis Oncology for 20 years and GSK Oncology for four years. At Novartis, he contributed to bringing the second ALK inhibitor to market.

Dr. Culver retired twice—but found himself repeatedly called back to the medical field. He was drawn to ALK Positive, a patient-driven group that provides support, empathy, and research funding to change the future for all people with ALK-positive lung cancer. Says Dr. Culver:

“ALK Positive is very unique as a patient-driven, patient-led, and patient-funded organization. You can’t get much closer to patients and their needs than being with them every day. That is incredibly powerful and motivating, and it’s inspiring to work with them. When I came onboard, ALK Positive had already set up medical committees of patients and caregivers, including the Research Acceleration Committee. We speak to biotechs about why ALK-positive lung cancer should be part of their development portfolio. Our goal is to expedite therapies that can halt progression and eliminate any remaining microscopic cancer cells. Prevention of progression is always going to be better than trying to treat when tumors start growing again.

One of the points we make is that there’s a clear patient case in unmet need because nobody with metastatic ALK lung cancer is cured. Many ALK-positive patients live for a long time, but most of these patients are living with measurable tumors disease by scanning. This clinical stage is called MRD (minimal residual disease) setting. So, in talking to biotechs, we can say that you can develop a treatment for patients in this minimal residual disease. The goal being to clear any remaining tumor deposits on the scan and the remaining microscopic cells We can also make a clear medical case because the biology of ALK is different from other forms of lung cancer such as KRAS, EGFR, and ROS1.”

Through his work at ALK Positive and with the Research Acceleration Committee, Dr. Culver also searches for gaps in research. Part of the MRD process is that “persister cells” aren’t killed off with chemotherapy, radiation, or TKI treatments. Instead, these cells go into a dormant state. 97% of patients with late-stage ALK-positive lung cancer are in this MRD state. Uncovering ways to eliminate the persister cells could significantly benefit patients and, says Dr. Culver, is an attractive prospect for biotech companies.

One of the reasons why Dr. Culver is so committed to pushing for research is to diversify what options patients have and to do his best to support the ALK-positive community. He shares:

“I began working with these wonderful people at ALK Positive and falling in love with them. I want to find ways that can help them now. Research is great but if it takes ten years, few of the people I work with are going to benefit from it. My goal is to see what we can get into clinical studies sooner, as well as embarking on longer research projects. Two examples are collecting single-cell RNA data to see what is on the outside of ALK-positive cells, as well as collecting a list of every FDA-approved drug, regardless of disease state, and attempting to match those to other genes expressed in ALK cells to identify potential drug combinations.”

The Phase 3 ALINA Trial

To Dr. Culver, the results of the Phase 3 ALINA study show how promising Alecensa could be in treating ALK-positive NSCLC. The study focused specifically on the sub-population of early-stage cancer. Dr. Culver explains:

“In ALK-positive lung cancer, about half of patients are diagnosed with metastatic disease. Research has mainly focused on that group. There are 30-40% who have stage 1B to stage 3 with resectable cancer, but there has not been a systematic study done with TKIs in that group. Genentech, seeing this unmet need, ran the ALINA trial to specifically compare the standard-of-care (chemotherapy) vs. alectinib, which is a fantastic drug that was originally approved in the metastatic setting. The study comprised 170 sites in 30 countries and the data is spectacular.”

Researchers have long known that chemotherapy is not incredibly effective for early-stage ALK-positive NSCLC. Despite chemotherapy treatment, the risk of disease recurrence remains high (~45–76%, depending on stage). This is a significant issue for the ALK community as up to 40% of ALK patients are diagnosed in these early stages. While the reported data from the ALINA trial is not yet five years out, Dr. Culver describes the data we do have as transformative and practice-changing, saying:

“At 2 years, 93.8% of patients had no cancer recurrence. Alectinib also improved disease-free survival by an unprecedented 76% compared to chemotherapy. ALK-positive lung cancer has a high rate of metastasis to the brain, which is normally treated with radiation. In this trial, we also saw that alectinib was highly effective in controlling and decreasing brain metastases in early-stage patients.”

Dr. Culver does acknowledge that there are still some unknowns: what happens if the cancer recurs, the overall survival benefit, and whether two years is sufficient to get the maximum impact of alectinib in early-stage ALK-positive NSCLC. However, he shares:

“As an ALK-positive community, we are ecstatic. There is a high expectation that alectinib will advance life for years in this specific patient group. Thank you, Genentech, for investing and improving outcomes for thousands of ALK patients.”

Based on the data, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted Priority Review to Alecensa for this population. A decision regarding approval is expected in May 2024. Says Dr. Culver:

“I think it’ll be a relatively easy decision. Alectinib has an established safety and efficacy profile with nothing that says there’s any new risks for this population. Physicians also already know how to use alectinib.”

That being said, Dr. Culver believes that to truly benefit people with early-stage ALK-positive NSCLC, it is imperative that doctors begin testing for genetic causes of lung cancer. He shares:

“If you have a new lung cancer patient and you remove the cancer but don’t test it for ALK, you could be preventing that patient from receiving the care they deserve. That could be a loss of many years of life for an ALK patient. Every person with lung cancer, regardless of stage or histology, needs to be tested. To me, that’s the entire oncology community’s responsibility to make sure that happens. If I had a magic wand to help lung cancer patients, that’s what I’d wave it for: that everyone would get tested and everyone would get cured. But you cannot cure patients if you don’t know what they are dealing with.”