Rare Community Profiles is a Patient Worthy article series of long-form interviews featuring various stakeholders in the rare disease community, such as patients, their families, advocates, scientists, and more.

Advocating for Access to Orphan Drugs: How Beth and Madison Advocated for Public Funding for the First Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Modulator in Canada

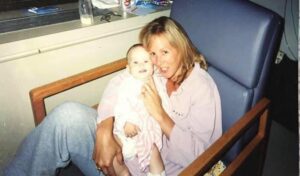

When Beth Vanstone looks at her daughter Madison (Madi), now a brilliant 22-year-old woman with a zest for life, she can’t help but smile.

Over 20 years ago, when Madi was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis (CF) at just eight months old, the family didn’t know what to expect. There was no newborn screening at the time. Madi wasn’t diagnosed until she was hospitalized after her first exacerbation, or severe lung infection. As Beth reflects back on that day, she says:

“Our life changed that day. At the time, there was not a lot of hope for people with cystic fibrosis—just a lifetime of adding therapies and drugs, constant hospitalizations, and an extremely shortened lifespan. It was heart-wrenching to get the diagnosis.”

Despite the challenging news, Beth and her family were prepared to fight. They did not sit back and wait; they jumped into fundraising, awareness, and advocacy as soon as they could. Madi began participating in every clinical trial possible. Says Beth:

“Our goal was to evoke change and make things better for everyone living with cystic fibrosis.”

Madi grew more and more ill. As she grew older, she was hospitalized at least twice each year for two or more weeks at a time. She often missed school. Feeling poorly meant that she couldn’t spend time with family and friends. By the time Madi was a teenager, doctors were already discussing how she might need a possible lung transplant.

Then came Kalydeco, the first CF modulator and CFTR potentiator that Canada had seen. The trial transformed Madi’s health but gave the Vanstone family deeper insight into drug policies in Canada.

Recently, Beth sat down with Patient Worthy to discuss her family’s experiences, drug access issues in Canada, and how to become a strong advocate.

What is Cystic Fibrosis (CF)?

Cystic fibrosis is a progressive genetic condition that causes respiratory and digestive system damage. This condition results from CFTR gene mutations. Normally, this gene helps regulate salt movement throughout the body. These mutations mean that mucus in the body becomes thick and sticky, clogging up airways, trapping bacteria, and preventing the release of digestive enzymes. Cystic fibrosis is a variable disorder; signs and symptoms vary based on severity. Potential symptoms can include:

- Persistent coughing and wheezing

- Shortness of breath

- Poor weight gain

- Difficulty exercising / exercise intolerance

- Intestinal blockage (in newborns)

- Salty-tasting skin

- Greasy and foul-smelling stools

- Constipation

- Frequent/recurrent lung infections

- Stuffy nose

A Worthwhile Clinical Trial

The clinical study that Madi enrolled in was blind, meaning the family did not know who was receiving the drug and who was receiving a placebo. However, within 24 hours of treatment, Beth and Madi were convinced that she had taken the drug—and that it was already doing amazing things for her. Beth explains:

“After a few days, she told me that she could breathe through her nose. She hadn’t been able to do that previously. Madi had been under the 5th percentile in weight for most of her life but was finally gaining weight. Her headaches and stomach issues resolved. In just 30 days of being on the trial, her lung function increased from 70% to 115% of the expected volume. It was fabulous to see her really go back to enjoying her life.”

However, the family faced a sudden and unexpected challenge when they tried to access the drug outside of the clinical setting. Beth explains:

“Canada has a very complicated drug pathway, especially for rare diseases. We were unaware. Like many people, we assumed that if you needed a drug, you could get it. Kalydeco was the first treatment of its kind and only 118 patients across Canada would benefit—but don’t these people and their lives matter?”

Madi and Beth battled for access. Beth explains that they held press conferences, gave interviews, and attended advocacy days at Queen’s Park. These experiences showed Beth that the drug approval and access process was not just difficult for cystic fibrosis, but for all rare diseases. She shares:

“It was eye-opening for me and quickly changed the narrative from ‘we need to approve this cystic fibrosis drug’ to ‘the entire system needs to be changed to accommodate rare diseases and orphan drugs.’ Canada doesn’t have an orphan drug designation to help with this process. There are too many restrictive policies in place so that patients don’t get to see those drugs.”

After a public two-year battle, Health Canada finally approved Kalydeco in 2012 for people ages six and older with a G551D mutation in the CFTR gene. This approval has since been expanded to include children who are even younger.

Madi has performed wonderfully on Kalydeco and her health flourished. The family shared in a story with CTV News Toronto that Madi and Beth, to celebrate her newfound health, also traveled to and traversed the Great Wall of China, raising over $32,000 for Cystic Fibrosis Canada.

Fighting Bureaucracy

When asked why drug access is such an issue in Canada, especially for drugs related to rare disease, Beth mentioned that there is a lot of bureaucracy. She shares:

“I would love to see more collaboration in development, policy-making, and research to ensure access to the best and newest therapies for patients. We see a cold chill between manufacturers, government, and policy-makers here. If we could get people thinking about betterment for the patient population, we could improve quality-of-life. My goal, and the advocacy work that I do, is to break down existing barriers and create a more direct pathway for necessary medications in a timely manner. We want individualized pathways. If you have a child who needs a drug for SMA before they’re six months old, you cannot be in a system that takes years to grant approval to access. We can take lessons from around the globe where this process is going better and use tools like outcome-based agreements and real-world evidence to get quicker approval.”

Beth also encourages policy-makers, manufacturers, and government agencies to be more open to hearing from advocates and to truly take their thoughts into account. Advocates are sometimes invited to policy meetings and access discussions. But, says Beth:

“As a patient advocate, I feel like it’s a token invitation rather than an invitation to be heard. There are few questions and little follow-up—just so much resistance to change. We need these stakeholders to put down their walls and build trust. When it becomes adversarial, the patients lose out every single time.”

The Need for Continued Advocacy

Although Madi was able to access Kalydeco, many other patients across Canada still struggle with drug access. In the same news article from above, Madi and Beth discuss how Trikafta, another genetic modulator for cystic fibrosis, was approved in US markets in 2019. Canada did not gain access until over two years later in 2021. Says Beth:

“We continued to advocate on behalf of—and with—patients in a system that is so broken for rare diseases because we were watching people die who wouldn’t have died had these restrictive policies not been standing in the way of access. That has really motivated us to continue on this pathway to promote change in Canada and create pathways to access for patients who have no other hope.”

Beth and Madi have participated in advocacy through HAE Canada’s I Am Number 12 campaign. This campaign aims to:

“[elevate] the voices of individuals, or Changemakers, from across Canada to increase understanding and raise awareness of the fact that 1 in 12 Canadians will be affected by a rare disease in their lifetime, and also to highlight the importance of incorporating the Rare Disease Drug Strategy in Canada.”

Here, Beth offers a reminder that 1 in 12 is not nearly as rare as people think. More importantly, a rare disease can come seemingly out of nowhere and can happen to anybody; having support from your community and the medical sphere is invaluable. Says Beth:

“We had no cystic fibrosis in our family that we knew of, but here we are. You’re just living your life and boom – you’re part of the 1 in 12. And many people think that rare disease only affects the patient, but that isn’t true. The patient often carries the heaviest burden but rare disease affects the entire family. When someone in your family is diagnosed, you all help carry that load. We want other people to see that and to know that our voices matter.”

Advocacy Tips

As many people in the rare disease community know, it can be challenging to share your story or to get someone to listen and understand. Many people want to become advocates to create change and share their experiences but aren’t sure where to start. When it comes to being an advocate, Beth shares:

“Have your story. Understand the barrier. Offer a possible solution. Nobody knows your story like you do and your story will help impact change. It can be intimidating when you’re talking to pharma companies about access or pushing politicians towards change. But 90% of the time, you know more about the situation and barriers than they will.”

Relationship-building is also key. Beth explains that a centerpoint of her advocacy journey has been repeatedly connecting with policy-makers and members of Parliament who can support her efforts:

“It isn’t a matter of going in once and leaving it in their hands. You need to come back, re-address, and make them care. That’s part of my process of storytelling: sharing this journey and letting them know how to help. It’s the stories and patients that can really make a difference. Advocacy doesn’t have to be 24/7 but, depending where on the journey you’re at, reaching out and touching base every few months is important. Keep them up to date. Thank them. Gratitude is huge. Make them feel like they’re part of the solution.”

At the same time, Beth says, don’t compare your story or journey with anybody else’s because your journey is unique. She says:

“Sometimes dealing with a diagnosis is all that you can handle. That’s okay. If a diagnosis has come and it wipes you out and all you can do is stay afloat, focus on the problems at hand and reach out for help. If you have a local foundation, go there. If you have an ultra-rare condition, see if social workers or someone else can connect you to help. But don’t expect more from yourself than you’re able to give. Don’t expect to come into this situation and be the biggest voice or the biggest advocate. You have to give yourself grace that you’re doing all that you can. If you’re the best caregiver to your child, that’s what counts. Don’t put undue expectations on your journey.”