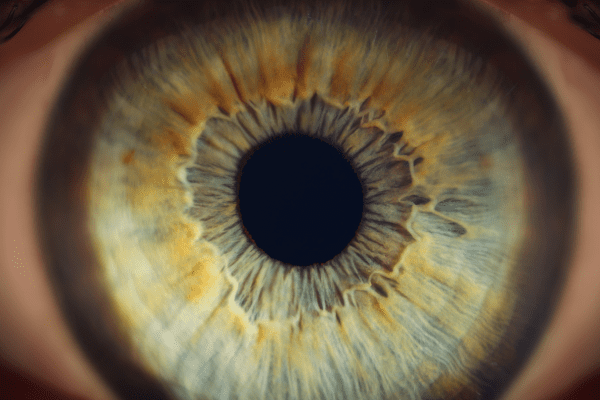

A UCLA Health study published on UCLAHealth.org suggests that numbers already used to gauge heart health may also offer an early warning for serious eye disease. Researchers found that a standard cardiovascular risk calculator, the Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE) score, can help predict who will later develop several potentially blinding conditions.

The team examined electronic health records from 35,909 adults aged 40 to 79 who were part of the All of Us Research Program between 2009 and 2015. Each participant’s PCE score was calculated using familiar clinical measures: cholesterol levels, blood pressure, smoking status, and the presence of diabetes. Based on this score, people were placed into four categories of 10-year cardiovascular risk: Low (under 5%), Borderline (5–7.4%), Intermediate (7.5–19.9%), and High (20% or more).

Researchers then followed participants over five to seven years to see who developed major eye disorders, including age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, retinal vein occlusion, and hypertensive retinopathy. To avoid confusing the results, they also adjusted for other influences not included in the PCE score, such as detailed racial and ethnic subgroups, body mass index, kidney disease, and educational attainment.

The analysis revealed a clear pattern: as cardiovascular risk increased, so did the likelihood of eye disease. Compared with people in the Low-risk group, those in the High-risk group were:

- 6.2 times more likely to develop age-related macular degeneration

- 5.9 times more likely to develop diabetic retinopathy

- 4.5 times more likely to develop hypertensive retinopathy

- 3.4 times more likely to develop retinal vein occlusion

- 2.3 times more likely to develop glaucoma

The PCE score was especially strong at identifying future cases of diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration, and these relationships held steady across different follow-up durations.

Because many of these conditions progress silently until vision is already impaired, using an existing cardiovascular risk score as a screening trigger could be highly practical. Primary care clinicians could flag patients in higher risk categories for earlier or more frequent comprehensive eye exams, without ordering new tests or investing in specialized technology. As senior author Dr. Anne L. Coleman noted, the necessary information is already embedded in routine medical records.

Future work will need to determine how best to act on this risk information: which patients should be referred, how often they should be examined, and whether earlier detection driven by cardiovascular risk actually reduces visual impairment. Implementation studies will be important for weaving this risk-based approach into electronic health records and everyday clinic workflows. If successful, a tool built for heart disease prevention could also become a powerful ally in preventing avoidable blindness.