Did you know estrogen can help protect the body from multiple sclerosis? A recent study by a team at UCLA solidified this finding and discovered how it works. Read on to learn more about this exciting development, or follow the original story here.

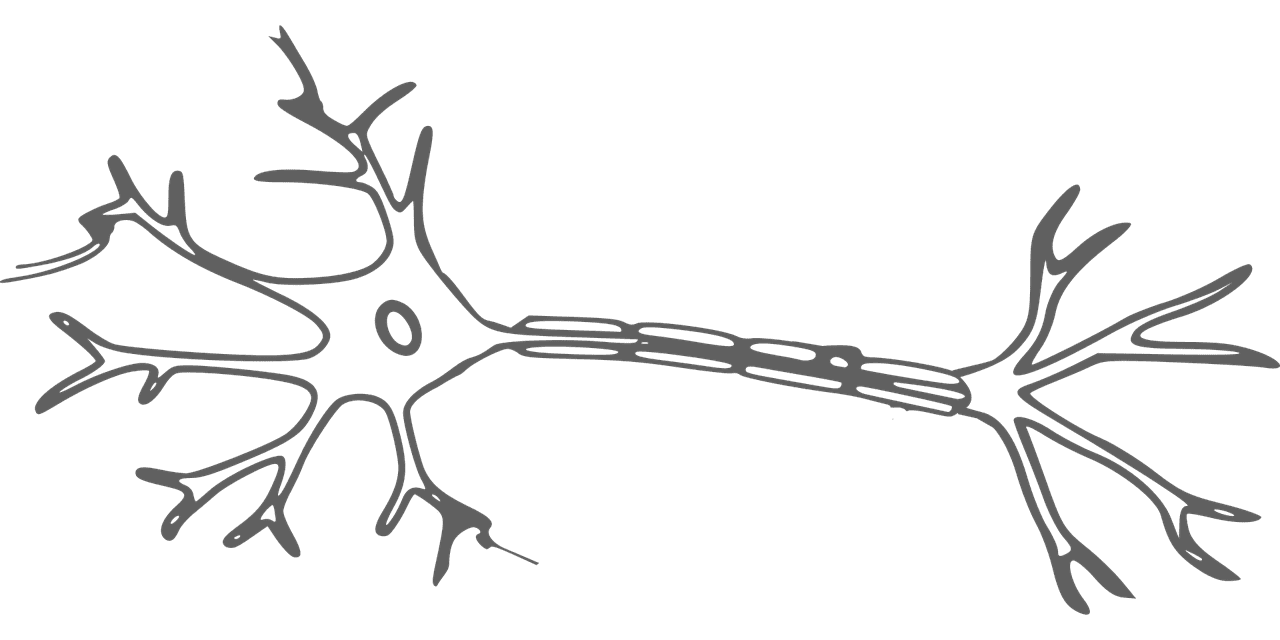

Multiple sclerosis is a disease in which the body’s own immune system eats away parts of nerves. More specifically, in cases of multiple sclerosis (MS) the immune system strips nerves of their protective myelin sheath. The destruction of the myelin surrounding nerves results in poor communication between nerve cells. Disrupted communication causes the chronic symptoms associated with MS such as weakness, sensory loss, cognitive impairment, and vision loss. To learn more about MS, click here.

You wouldn’t think that estrogen has anything to with that. However, the third trimester of pregnancy has curious effects on MS patients. The rate of relapse for MS patients during the third trimester is reduced by about 70% when compared to pre-pregnancy rates. Some studies have even shown that multiple pregnancies can have long term benefits for MS patients.

The main suspect behind this curious case is a unique form of estrogen produced by the fetus and placenta during pregnancy.

A team of doctors led by Rhonda Voskhul havs proposed this type of estrogen as a possible form of treatment. So far, they have successfully used it in mouse trials, and two completed clinical trials with human patients.

Until recently, however, the mechanics underlying the treatment remained unknown. This key piece of information has been uncovered in Dr. Voskhul’s latest study. While studying mice, Voskuhl reported that estrogen protects the brain from by triggering a protein called estrogen receptor beta. The new research also highlights which brain cells are involved and related to this protection.

Researchers tested this by removing estrogen receptor beta in either immune cells or oligodendrocytes (cells responsible for creating the protective myelin sheath). This would make cells in the MS test mice unresponsive to estrogen. Researchers would then treat the mice in each group to see what kind of disease protection, if any, existed. If the protective effect was lost during the treatment researchers would be able to confirm that the treatment was effecting the cells with the receptors removed.

Results of the MS mouse study showed that the new treatment was impacting both the immune cells and oligodendrocytes. The result of both of these cell types being affected is that disability can be decreased and myelin can be repaired.

Development is still ongoing, but the results are in. Dr. Voskhul and the research team are in pursuit of a new estrogen-like compound. Such a drug would be able to fight MS on two fronts and may be the next big step in treatment or finding a cure.